Sustainable Business as the Base for Sustainable Entrepreneurs: Some Theoretical and Practical Reflections

ARTICLE | July 25, 2018 | BY Zbigniew Bochniarz

Abstract

Threats to the sustainability of the Earth’s ecosystem are increasing. It is urgent that we prepare a cadre of entrepreneurs who, with an understanding of the complexity of sustainability, should lead organizations toward a sustainable future. The emergence of entrepreneurs in the sustainability field is critical not only for the business sector but equally important for the public and non-profit sectors. This paper focuses on business entrepreneurs utilizing both theoretical models and practical cases from research conducted by international teams of graduate students on selected international corporations. It starts with a brief overview of the evolution of sustainability, sustainable business and entrepreneurial concepts. Then the author moves on to an analysis of common and specific features of several cases of entrepreneurs who worked to make their companies sustainable. Finally, the paper analyses the effectiveness of delivery methods based on student-centered concepts implemented by creating a learning community with action research.

1. Introduction

There are many reasons to turn to entrepreneurs for solving complex sustainability issues. Following Albert Einstein’s thoughts, we cannot solve current problems with old approaches shaped by the past system that produced them. For that reason we need to create an innovative entrepreneurial approach based on human imagination and creativity—on Human Capital (HC). HC is the only creative form of capital. Since human creativity is unlimited, this is the most critical factor contributing to sustainability in general and to sustainable economic development in particular. For economists, effective and efficient resource allocation (different forms of capital) forms the basis for survival in the market and thus for sustainability. Limited resources and growing threats to sustainability require a new form of entrepreneurship that will meet basic human needs and reduce environmental threats by offering innovative and sustainable allocation of available resources.

Although the term “entrepreneurship” originally came from business, these days we see more social entrepreneurs. For this reason, it is important to define a universal term of entrepreneur as an agent who takes the risk and responsibility for managing resources to deliver services beneficial to its stakeholders. Currently most resources are allocated in the private (business) sector, e.g., according to M. Porter’s (2013) research on the US economy, the private sector controlled $23TR (measured by revenues), the government (public) sector controlled only about $3TR (expenditures), and the civic (NGO) sector’s share was about $1.3 TR (outputs) in 2013.* Although this allocation may differ in each country, it seems to accurately reflect the global economy. Based on this assumption, I argue that the most critical challenge is to use private sector resources in the most sustainable way for the sake of the planet. I believe that converting business as usual (BAU) into sustainable business (SB) is a primary way to build sustainability. There are two major ways to do this: using external forces—governmental regulations (command and control), market-based incentives, and civic pressure (mainly via non-governmental organizations—NGOs), or by internal forces that bring the necessary change from within companies. Arguments for the approach based on internal forces come from the megatrend of the growing significance of multinational corporations (MNC) on the global market, which are difficult to influence by specific national policies. So far the external multinational or global institutions protecting the Earth’s sustainability are rather weak and not sufficiently effective. For that reason we need to complement them with internal forces that are sensitive to the peer pressure of other competing MNCs. Notably, during the last 16 years the number of companies that have signed the UN Global Compact increased from 100 in 2001 to 350 in 2011 (UN Global Compact-Accenture CEO Study 2010), and to 9,000 in 170 countries in October 2017 (www.unglobalcompact.org 2017).

The literature is full of descriptions of different policies influencing business behavior, their effectiveness and costs. Significantly fewer publications are devoted to the role of civic sector, but still one can find many examples of successful actions. However, both approaches have one major disadvantage: They create an adversarial relation with business due to their external nature. In the last 10-15 years, many successful initiatives have established public-private partnerships (PPP) to resolve serious environmental or social problems, but they are still external forces that are not always well-received by business. For that reason, there is urgent need to explore the second approach by applying internal forces. This approach will not only remove the above mentioned disadvantage of the first approach, but it will create a significant advantage in the form of pride and ownership in the transformation to SB. In order to make it, we need to educate entrepreneurs—by investing in human capital (HC)—to lead their businesses toward sustainability. The above cited Accenture Study of CEO (2010) indicated that 90 percent of them believed that sustainability was important to company profits and 72 percent said that investing in education was critical for them to succeed in making their business sustainable (ibid.).

There are many ways of investing in HC. Educational institutions can play a crucial role in shaping new HC, particularly in higher education. Although many successful entrepreneurs—Gates, Jobs or Zuckerberg—are college dropouts, there is a bulk of literature showing that a solid higher education contributed to successful business or professional careers (e.g., Michelacci, 2015; Zumeta et al., 2012). Among academic institutions, business schools play a special role in educating entrepreneurs. For that reason, it is interesting how they treat sustainability courses in their curricula. Current research by A. Hoffman (2017) indicates the tremendous dynamics of business school courses incorporating sustainability into their MBA programs—a four times increase from 2001 to 2011. In addition, school participation in teaching sustainability in all types of business education has increased from 34 to 79 percent (Hoffman 2017, 280-281). The author presents two models of teaching business sustainability: The first is “Business Sustainability 1.0: Enterprise Integration” based on adapting sustainability principles into preexisting company conditions in order to remain competitive in the market, and the second is “Business Sustainability 2.0: Market Transformation” focused on systemic enterprise transformation including its role in society (ibid. 279-286). To more easily understand the differences between these two models he characterized them after J. Ehrenfeld (2008), as “reducing unsustainability” with the first model, and “creating sustainability” with the second model (ibid.). From the perspective of external and internal forces, the first model would mean an adjustment (from non-compliance to compliance stage) to the external factors and the second, an internal transformation toward sustainability.

From the business school point of view, they face the dilemma of which curriculum they should teach: business integration or market transformation. Logically, they should start with business integration to stop unsustainable practices, reduce or neutralize external pressure and negative externalities and then move on to design a transformation in the companies considering sustainability. If we look at the implementation process of company integration, we could treat it as a learning process to adjust to the external pressure coming from four different types of “drivers” according to A. Hoffman (ibid. 281):

- Coercive drivers – domestic and international regulations and courts

- Resource drivers – suppliers, buyers, investors and financial institutions

- Market drivers – consumers, trade associations, competitors and consultants

- Social drivers – environmental NGOs, media, religious and academic institutions.

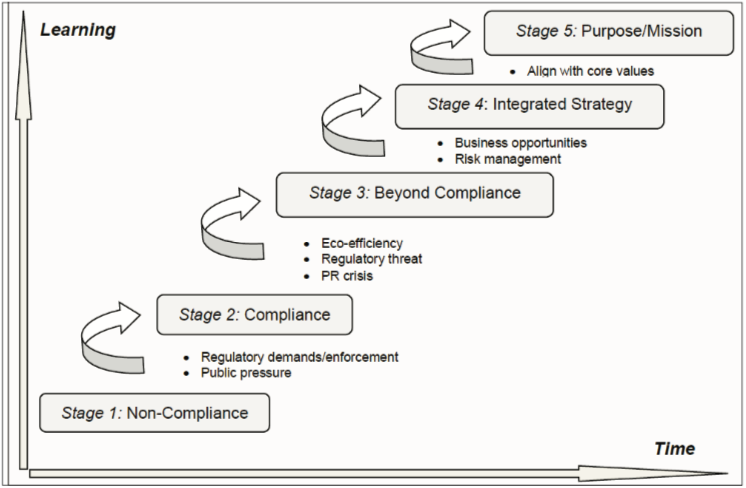

2. Defining Sustainable Business

In management literature, this learning process is described as the three phases of the sustainability continuum (Rejection, Non-Responsiveness, Compliance/Risk Reduction) by Dunphy and Benveniste (2000) or by the two initial stages (Non-Compliance and Compliance) by Willard (2005) and Senge (2008), who regarded the whole process as developing a learning organization. Figure 1 illustrates the process of company development from an unsustainable stage to a sustainable stage (Willard, 2005).

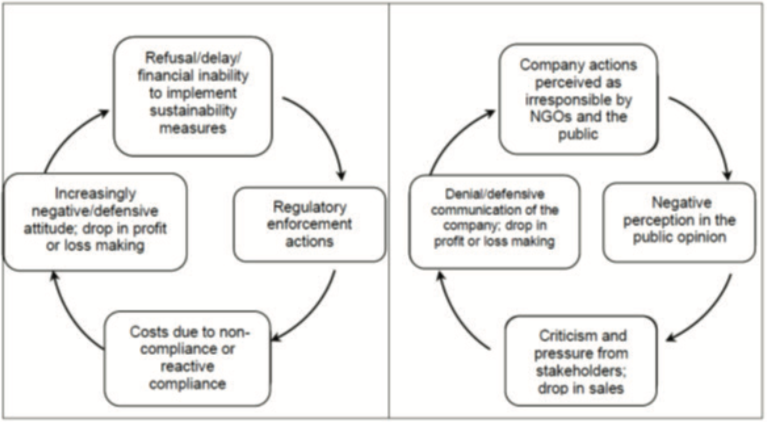

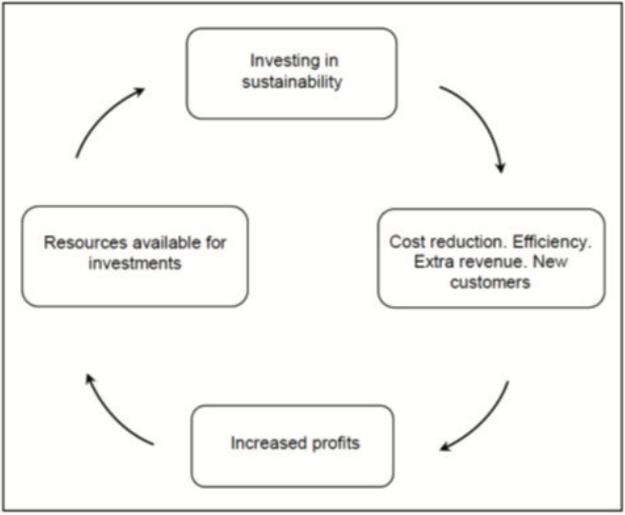

Summarizing the first stages of enterprise development from existing literature, Oncica and Candea (2016) indicated that this is a reactive change made under external pressure and is usually coupled with very expensive direct and opportunity costs. They note a proactive approach would allow companies to link changes with the benefits of their entrepreneurship and innovations. Many companies get stuck in the first two stages in a Vicious Cycle described by them (see Figure 2). The authors—Oncica & Candea—using the tools from System Analysis illustrate reinforcing loops that are vicious from the point of moving toward sustainability because they represent the factors opposing or at least delaying the process of implementing sustainability policy measures (ibid. 17). From that point of view the most critical stage is the transition from stage 2 to stage 3: Beyond Compliance (Figure 1). Here is a chance to gather momentum and move forward with the implementation of sustainable policy measures by observing when emerging impacts of the transformation—efficiency gains, declining costs and growing reputation—balance or exceed initial investments (Senge et al. 2008). Oncica & Candea illustrate this process by reinforcing loops in the Virtuous Cycle that supports the drive toward sustainability—Figure 3.

Source: Willard (2005), Senge et al. (2008)

Source: Oncica & Candea (2016, 17) after Senge et al. (2008) and Willard (2005)

Source: Oncica & Candea 2016, 18

The central point of this paper is that at this stage of enterprise development, the entrepreneurship phenomenon is emerging to meet challenges by entering new territories—going Beyond Compliance to start building sustainable business. The most popular meaning of entrepreneurship is “the activity of setting up a business or businesses, taking on financial risks in the hope of profit” (Oxford Living Dictionaries 2016). The most critical characteristic of entrepreneurs is taking a risk for future gains, which might also lead to failure with losses of capital or even bankruptcy. Entrepreneurs, contrary to managers or other employees, take the risk of losing not only their incomes but their property and career. There is a limited pool of people with natural entrepreneurial abilities who are also responsible risk-takers. The business education process can further expand the pool by producing HC equipped in entrepreneurial knowledge and skills to facilitate the process of moving firms to stage 3.

Although it is challenging to move to stage 3, the authors—Oncica & Candea—underline that moving from stage 3 to stage 4 (Integrated Strategy) marks “a real qualitative leap: it requires the ability to link market opportunities with corporate responsibilities” (ibid.18). This is a challenging stage demanding “creative destruction” leaps by innovative discontinuity of existing industrial processes and product design enriched by sustainability values (Willard 2005, 29). “Moving from stage 3 to stage 4 requires internalizing sustainability notions in profound ways, both personally and organizationally. […] Sustainability-based thinking, perspectives and behavior are integrated into everyday operating procedures and the culture of organization” (ibid.). According to Willard (2005), companies in stage 4 and stage 5: Mission/Purpose look similar but differ with their motivation. “Stage 4 companies ‘do the right things’ so that they are successful businesses. Stage 5 companies are successful businesses so that they can continue to ‘do the right things’” (ibid.). Moving from stage 3 through stage 4 and 5 requires not only Schumpeterian “creative destructors”—entrepreneurs—but also visionary leaders who are able to articulate an ambitious vision for the firm, and also mobilize employees to follow its new mission toward reaching new values and establishing a new corporate culture embracing sustainability. This deep business transformation is a complex, risky and time consuming process. Education can facilitate the expansion of currently limited HC with the leadership knowledge, skills and attitudes to embrace sustainability.

Stage 3 in the Willard model indicates the beginning of the sustainability transformation process described by Hoffman as “market transformation” of the company. For Hoffman, in writing about Sustainability 2.0, the most important factor is focusing on transforming business education that needs a systemic approach, bringing radical changes to curricula and delivery methods based on the new conceptions of the following components (Hoffman 2016, 283-7):

- Market parameters – e.g., “malleability and multiple forms of capitalism”

- System parameters – holistic, systemic approach with company as a part of the system

- Operational parameters – e.g., optimizing supply chain logistics

- Organizational parameters – hybrid and networked organizations

- Business metrics and models – “from regenerative capitalism and collaborative consumption to conflict-free sourcing and environmental finance”

- Redefinition of the role of companies in society – redirecting business to play a positive role in resolving serious challenges facing society.

Responding to the growing demand for sustainability courses from executives and students (particularly after the 2008 financial crisis), the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) created new standards for social and environmental sustainability (based on Sustainability 1.0) that accredited schools were required to implement by the school year 2016-2017 (ibid. 287). Hoffman regards this as the first step in institutionalizing sustainability teaching, which will have to follow with the Sustainability 2.0 courses that are real market transformation drivers. He also believes that the market (comprising resources of business, government and civic organizations) is “the most powerful organizing institution on Earth and corporations are the most powerful organizations within it” due to their abilities to innovate, produce and distribute. For that reason he concludes that “if there is no solution coming from the market, there will be no solution” (ibid.).

Now that I have explained the process of transforming companies to adapt sustainability and how to organize teaching, one may ask what a sustainable business (SB) is and how it contributes to sustainable development. No doubt that the 2008 financial crises and the Great Recession following it brought the issue of sustainable business (SB) to the forefront for many constituencies, but with many different understandings of the term (Oncica & Candea 2009). For some SB means survival of the market (Werbach 2009), for Porter & Kramer (2011) it means staying competitive by creating shared values (CSV), for others (Wilson 2003; Candea & Oncica 2008; Rok 2014) SB is a complex and evolving term based on five pillars: 1) Sustainable development, 2) Environmental management, 3) Stakeholder theory, 4) Corporate social responsibility, and 5) Corporate accountability.

In the recent synthesizing study on SB, Oncica & Candea defined sustainable business as

a business that is prosperous in the long run, which makes it able to provide its shareholders, for an indefinitely long time, with a fair return on the invested capital. In order to approach this ideal, the company should strive to develop a strategy that integrates business objectives with consideration for the needs of a wide range of stakeholders, selected on relevance criteria. This way, the strategy of a sustainable business will eventually include objectives that concern all three pillars of sustainable development: economic, social and environmental (ibid. 98).

The authors treat business sustainability as a continuous process of transformation, of learning, of organizational becoming (ibid.). Based on their studies, they developed “a model that consists of five stages in the evolution of integrating sustainability in the strategy and values of an organization” and reveals the progressive stages in which contemporary enterprises may find themselves in terms of their commitment to becoming sustainable (ibid).

Source: Oncica & Candea (2016, 120)

Quite a comprehensive presentation of the Oncica & Candea model of SB influenced by the leading thinkers in management sciences, particularly by Senge’s concept of learning organization, this model is motivated by the fact that it was selected as the leading model applied in graduate student action research within the course of “Building Sustainable Business” at the Kozminski University in Warsaw, Poland, in spring 2017. The authors—Oncica & Candea—applied the concept of learning organization to strategic management to reconcile short- and long-term shareholders’ interests. In addition they incorporated the idea of the knowledge spiral from Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) in their model illustrated in Figure 4. Oncica & Candea show two interrelated levels—level “0” combining the learning cycles based on the “knowledge spiral” and cycles taking place in team and community practice introduced by Senge (2006). They explain that the “cycles underline the other elements of the model situated at level ‘1,’ i.e. four disciplines of the learning organization and the strategy development” (ibid.120). Finally, the authors conclude that the learning process at the “0” level creates the base for developing SB.

In summarizing this methodological section, it is important to note that sustainable business is not a substitute for sustainable development or the Earth’s sustainability, but without businesses that are involved in moving toward sustainability in a strategic way, we cannot sustain our life on this planet.

3. Sustainable Development, Sustainability Science & Institutions for Sustainability

The term “sustainable development” came from the report Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (1987) authored by Norwegian Prime Minister G. H. Brundtland and prepared for the United Nations’ Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), held in Rio de Janeiro, in 1992. The report came up with the most popular definition of the term over the last 30 years: “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (ibid. 43). Despite its popularity, it was not easy to operationalize it and implement it in practice at different levels of human activities. One of the most popular ways was implementing the principle of the triple-bottom-line (TBL)—economy-environment-society—to evaluate the sustainability of business or public actions. It was not precise but at least led to the consideration of three major dimensions of any activities. To make it more precise, economists developed two basic approaches to measure sustainability: one based on human material wealth maximization (MWM), usually measured by the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, and the second based on maintaining non-declining total capital (NDTC). So far, the first approach has been the most popular, but its deficiencies have been obvious since it was introduced by S. Kuznets (1937), and its critics are growing year by year (e.g., quite recently by Stiglitz et al. 2008). Knowing these GDP deficiencies, American economists R. Solow (1972) and J. Hartwick (1977) suggested that there is another way of sustaining human wealth—by maintaining non-declining total capital under certain conditions. One of the strong supporters of NDTC was the British economist D. Pearce, who proposed a transitional sustainability indicator from MWM to NDTC in the form of genuine savings (GDS) or slightly modified as adjusted net savings (ANS) in 1994. He has also convinced the World Bank to include ANS in its Statistical Yearbook since 1999. The ANS, contrary to GDP, includes changes in human (HC) and natural capital (NC) in the form of investments in HC and decreases in NC by extraction of minerals, energy resources and damage caused by climate change (depletion rents)†. The significance of the introduction of ANS was the inclusion of two additional forms to man-made capital (Km)—HC and NC. Although this is still an indicator based on gross national income (GNI), which came out of GDP, it was a big step forward in the way of thinking about sustainability.

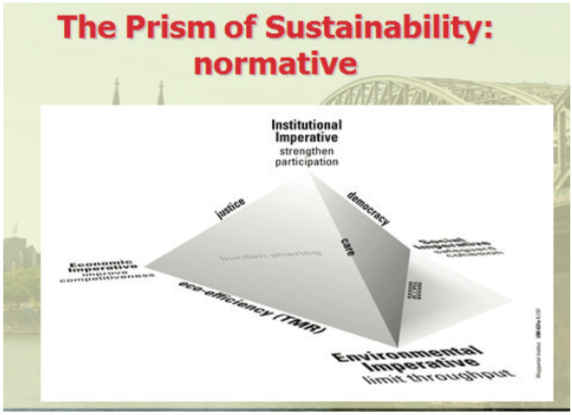

Source: Joachim H. Spangenberg Sustainable Europe Research

Institute (SERI) Germany (2016)

Thirty years later, after the publication of the Brundtland Report, we are much better equipped to measure sustainability. Since 2001 we have a new discipline—Sustainability Sciences, which is an interdisciplinary, holistic science offering many interesting approaches to assess and measure sustainability (Kates et al 2001; Spangenberg 2011). Spangenberg (2005) asserts deficiencies in operationalizing sustainability using the TBL approach and suggests a substitution by quadruple bottom line (QBL). He gives convincing evidence that the fourth dimension of SD should be an institutional dimension—securing democracy, justice and care—Figure 5. It is noteworthy to add that well-designed institutions—mainly norms and rules—influence the transformation of people’s attitudes and habits (an important feature of HC) toward those desired by society, and this way are becoming values—building blocks of a new culture. For that reason sustaining an institutional base is critical for sustainability in general at any level of human activity, from communities and firms to national and world-wide levels. Institutions as social inventions are results of human relations, and interactions contribute to the wealth of nations (Bellah et al., 1992; Bolan & Bochniarz 1994). The more time people spend on building relations, the more they invest in their social capital (SC), which in turn produces better norms and rules, trust and values such as mutual respect, loyalty, tolerance and common goods (Bochniarz 2008, 2016). This way the strength of institutions depends on the value of SC invested.

During the last 20 years the popularity of SC has increased tremendously in social sciences publications. From the economic point of view, its place and relations with other forms of capital were often not clear. Recently, economists (Goodwin 2003) and representatives of management and other sciences from the Sigma Project (2003) proposed a convincing model studying the relationship between SC and traditional forms of capital—HC, NC, manufactured capital (MC), and financial capital (FC)—Figure 6. They show the growing significance of SC, particularly in advanced economies. One can observe this phenomenon in many levels of human activities—from local to national and even international or in business, government or civic sectors.

Source: The SIGMA Project (2003)

In the recent years after the financial crisis of 2007-2008 and the following recession, we observed a huge wave of populism often combined with nationalism, or even fascism, worldwide, threatening democratic institutions, culture of fairness and care, and creating serious challenges to sustainability. Introducing the QBL is critical these days at every level of human activity and in each sector. This is a significant step far better than TBL in assessing sustainability.

In a series of articles, an international research team led by Archibald & Bochniarz (2003, 2005, 2008 & 2009) argued that at least 10 Central and East European countries (CEEC-10) made significant progress—based on the TBL—in their transformation from totalitarian political systems with centrally planned economies to democracies based on market principles since the beginning of the 1990s, and particularly after joining the European Union in 2003 (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia & Slovenia) and in 2007 (Bulgaria and Romania). The team concluded that those CEE-10 completed their systemic transformation and started moving on a sustainable path of development (Archibald et al. 2009). However, recent developments since 2010 indicate that after many successful years, some of them (Hungary since 2010, Poland since 2015, and probably the Czech Republic since the fall 2017 election) are being taken over by the populist-nationalistic wave with significant changes in their basic institutions, including their constitutions (in legal or illegal ways) and basic rules of law. In Poland for instance, the ruling coalition led by the Law and Justice Party (PiS) started to dismantle the independence of the Constitutional Court by replacing—mainly illegally—its independent judges by their own loyalists just after the parliamentary election in Fall 2015. By 2017 they succeeded in completely subordinating the Court to the executive branch of government despite numerous actions of parliamentary opposition parties, country-wide protests and interventions from the European Commission and the International Venice Commission comprised of prominent European and American judges. Today nobody can challenge the Polish Government of the constitutionality of its activities, including passing new laws, regulations and many other decisions.

Last July the government used the superfast track of the legislative process, passing three basic laws that de facto changed the Polish constitutional order—the Common Court System, the Country Justice Council (KRS) and the Supreme Court—by simple majority rules in the Sejm (Parliament) and Senate, bringing fundamental changes to the country’s political system in just two weeks. Both the process and the contents of laws violated the Polish Constitution and the basic parliamentary procedures in many areas, among others by excluding opposition parties from discussion and nongovernmental organizations from consultations. Although the President, who is also from PiS, initially vetoed two of those laws (those two significantly limited his power in favor of the General Prosecutor), the Common Court System law was signed by him and went into effect on September 1st. Two other laws after negotiations between the President and the PiS chairman J. Kaczynski—the real policymaker—went again through the parliamentary amendment process, were passed by the ruling majority and signed with several insignificant changes, shifting some power from the General Prosecutor to the President and Parliament on December 20, 2017.

Since September 1st 2017, over 130 heads and their deputies of regional courts have been fired without any comments or justification and new judges have been appointed, who are loyal to the General Prosecutor, who is also the Minister of Justice. The justice system is losing its independence, as it is subordinated to the executive branch run by one party interest. Basic values like rule-of-law are disappearing step-by-step, the nation is deeply divided, scared and insecure, including private business, who cut their investments to the lowest point in a decade (this is a significant threat to sustaining manufactured capital—MC). Economic growth is mainly fueled by consumption expenditures financed from budget transfers (mainly by the “500+” program for about 3.5 M people with multiple children), which was instrumental in granting the PiS election victory in 2015.

In addition, the recently introduced government “education reform” is trying to recreate the structure of the Polish K-12 system in the 1980s (8+4) with old traditional ways of teaching based on teacher-centered approaches. Critical and integrative thinking was replaced by extended national historical curricula and religion classes at each level, creating the potential for long-lasting damage to the country’s human capital (HC). Natural Capital (NC) is also victimized by the current government which introduced massive “sanitary” cutting in Europe’s oldest ancient forest “Puszcza Bialowieska” protected for conservation by Polish and EU laws, and despite massive protests from academia and NGO communities, EC & UNESCO, the trend had been continuing until the government was changed for another PiS based but more technocratic at the beginning of January 2018. Finally the aggressive xenophobic propaganda exercised by the government controlled media against opposition parties, intellectual elites, refugees, neighbors and the European Union (EU) destroys the social capital (SC) that slowly grew after the transformation. This path of development cannot be sustainable until the changes introduced by PiS are reversed. So far, the larger part of the nation—but without sufficient representation in Parliament—is not giving up but when they will win, nobody knows at this point.

This brief case study shows that Poland, which experienced the fastest economic growth among CEE-10 from 1992-2015 and often was exemplified by international organizations as the leader of the transforming economies in CEE, could easily damage its image and destroy its basic civic culture based on democracy, freedom, openness, mutual respect and tolerance for diversity by ideologically motivated institutional changes. This example underscores how important the fourth dimension of sustainability is and the need to operationalize it by the QBL, not only at the national level, but also at the regional, local, community and enterprise levels.

4. Lessons from Selected Cases

4.1. Assumptions, Organization and its Implementation

The lessons presented below come from the recently held graduate course on “Building Sustainable Business” at the Kozminski University (KU) in Warsaw, Poland. The main goal of the course was providing the knowledge and skills necessary to sustain business in the face of global competition and create positive impact at the level of a firm, region or country. The design of the course was student-centered and the role of the instructor was as a facilitator of building the learning community. All participants were treated as equal partners, who contributed to the community based on their knowledge, experiences and skills. The course was based mainly on cases with an introductory theoretical element from the recently published book by Oncica & Candea (op. cit.)—selected chapters—and two chapters from the instructor’s publications.

There were 11 cases discussed in the class, 7 of them based on students’ field research projects elaborated by 3-5 person teams. The quality of the project was equally important as the active class participation. From 38 initially enrolled students, 28 completed and passed the minimum requirements of the course. It was a very international cohort with only 9 students from Poland, and 17 from other European countries (including 13 from Ukraine), 8 from Asia and 4 from N. America. The students had to build and exercise their soft skills and competencies—including entrepreneurship and leadership—by selecting areas of their projects, designing their own team “constitutions” to effectively manage the project, conduct interviews with stakeholders, distribute team work according to their best capacities and prepare policy recommendations. Two of the stakeholders (from different projects) participated in final presentations and one of them delivered a guest lecture. The instructor conducted two anonymous team member performance evaluation (one in the mid-semester, one after project completion) and provided written guidelines for the contents of the project and for effective team presentations. At the end of the course an anonymous instructor performance and course evaluation was conducted with an average score of 4.4 points out of 5 maximum points.

4.2. Identifying Sustainable Entrepreneurship in Selected Cases:

4.2.1.The Nike Case

The Nike case was elaborated by Oncica & Candea (op. cit.) and was treated as a role-model for the students’ projects. This is a perfect case to teach sustainable entrepreneurship because it is the story of two business partners—Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman, who with an initial $500 in capital established the company in 1964, which became within just a few decades the leading global corporation in the industry (ibid). The case covers over 20 years from 1992 until 2012, showing how the company was struggling to climb the 5 stages of the sustainable business ladder (Figure 1. Willard and Senge, op. cit.). In order to better understand the company milestones to sustainable business (SB), the authors divided two decades into three periods with specific names: 1992-1998 “Social Challenges,” 1998-2005 “Business Integration” and 2005-2012 “Positive Vision” (ibid. 175). Probably under the influence of the 2nd Earth Summit in 1992 and significant involvement of big corporate involvement, Phil Knight, then chairman and CEO, established “The Nike Environmental Action Team” (NEAT) to monitor environmental compliance. The same year, they formed a three-person team to deal with the program called “Reuse-a-Shoe” and started collaboration with Paul Hawken—an American guru of environmental sustainability to educate the NEAT team. These decisions show the company leaders were open to new ideas, a characteristic of successful entrepreneurs. They also took concrete steps to learn about environmental threats and implement policies to reduce or eliminate them. One of the results of the “community learning process” was adaptation of The Natural Steps (TNS), one of the most popular worldwide frameworks institutionalizing company sustainability principles and culture in 1998 (ibid. 176).

Although the company was progressing fast by managing environmental issues, social issues became a big challenge. As a typical apparel and footwear company, Nike relied heavily on outsourcing manufacturing in developing countries without any control or interest in work and safety conditions. As one of the most recognizable brands in the industry with high financial performance, Nike was on the radar of global NGOs and media who brought to light their serious violations of labor standards since the early 1990s until 2002. The initial reaction of the leadership was defensive, presenting the company as a design and marketing corporation and not responsible for the working condition of their production suppliers. Particularly painful for them was Michael Moore’s documentary film “The Big One” in 1997 showing not only poor working conditions but also exploitation of child labor. Phil Knight in his angry reaction told Moore to report Nike to the United Nations (ibid.).

From the theoretical point of view presented earlier, this was a typical behavior of a company facing difficulties in breaking the Vicious Cycle (Figure 2). This arrogant response was probably a turning point in Nike’s defensive policy, when their own managers raised the issue as to why such an excellent company cannot take a proactive approach and effectively resolve such social problems in their supply chain (ibid. 177). Internal pressure started emerging to move out of the Vicious Cycle to the Virtue Cycle (Figure 3) and to the 2nd stage—Compliance—of building business sustainability (Figure 1). A few years later (2011), the Vice President of Sustainable Business and Innovation—Hannah Jones—stated that sharp critiques were “an early wake-up call to what become a greater wave of change… a massive revolution in the business community” (ibid.). So the boycotts and protests worldwide forced the leaders to change the course, who later on took corporate responsibility for social problems in 1998. Again Phil Knight announced in the prestigious National Press Club that Nike will make radical changes in treating their suppliers, imposing a series of reforms including the introduction of the Code of Conduct and a revised bonus system with respect to environmental and social values (ibid.) Nike took the risk of institutionalizing radically new values within the supply chain. This decision could produce not only positive but also negative effects, including cost increases due to internal monitoring and external auditing of implementation process, the possibility of production interruption due to elimination of some supplier who could not meet the requirements of the Code.

The next organizational activity was establishing the Corporate Responsibility Committee of the Board of Directors led by the Board member Jill Ker Conway in 2001. This was another step in institutionalizing environmental and social values, e.g., environmental stewardship and occupational health, at the highest level of company management (ibid.). The Committee also received the authority to oversee the publication of the first full-fledged CSR Report in 2001 adding additional important values—openness and transparency. These initial steps undertaken since 1998 indicate that Nike moved to building a new corporate culture aligned with the idea of sustainability. This way their CSR moved from tactical in the earlier stages to strategic after 2001, according to Porter & Kramer (2008). In the Willard-Senge ladder, the company moved to the 3rd stage—Beyond Compliance (Figure 1).

It is worthwhile to note that such risky and costly but fully entrepreneurial decision was unique in the footwear and apparel industries. Nike’s VP Hanna Jones was aware that those were costs of being an earlier leader in the industry, which could, however, stimulate company R&D and innovation (ibid. 179). One could say that it was a risky but effective investment in the sustainable future of Nike. In order to sustain the gains of this transformation, the company leaders took several steps to strengthen their business model, particularly in social areas by becoming founding members of the Fair Labor Association (FLA) and establishing the Global Alliance for Workers and Communities Foundation in partnership with the International Youth Foundation, MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank (ibid. 180). The first one—FLA—was an NGO organized in 1999 by human rights activists with companies, trade unions and other organizations focused on creating “lasting solutions to abusive labor practice by offering tools and resources to companies, delivering training to factory workers and management, conduction due diligence through independent assessments, and advocating for greater accountability and transparency from companies,… and others involved in the global supply chains” (FLA 1999– ibid.). The second—the joint foundation—concentrated on improving workers’ living conditions in emerging economies. Their particular interest was working and living conditions for young women who were composed of 80% of their suppliers’ employees. In order to address their needs, Nike financed a global survey of 67,000 female workers in their factories worldwide in their native languages and neutral locations. The Survey follow-up report and actions were made available to the public, particularly to other companies to follow Nike in improving working conditions (ibid.).

In addition to these two organizational efforts focused on social problems, the company leaders had established their own—the Nike Foundations—to support adolescent girls in poor regions worldwide to overcome poverty and gender discrimination in 2004 (ibid.). This way, according to Nike’s CEO, the company wanted to support the two UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and become an “engaged corporate citizen” utilizing the Foundation’s investment to initiate “a positive cycle of development, complementing, complementing the company efforts to improve its fundamental business practice” (ibid. 180-181). Taking into account these big social initiatives, one can conclude that Nike’s leadership moved further beyond strategic CSR to the stage of creating shared value (CSV), according to Porter and Kramer (2011). In the Willard-Senge ladder, the company moved to the 4th stage—Integrated Strategy (Figure 1). In order to complete the integration, Nike needed to bring together not only its top leaders but the whole staff – including managers and front line employees—to learn the new sustainable corporate culture. This was a complex process associated with high risks of failure. It required both visionary leadership and wise entrepreneurship, and a lot of patience.

It is interesting that Nike started building a long-term vision based mainly on environmental sustainability in 1995. The leadership role was taken by the Advanced Research and Development Division for Footwear department led by Darcy Winslow. They were responsible for identifying and analyzing new ideas, materials and technologies, which could bring disruptive innovations and create new development opportunities for Nike for the next 15-20 years (ibid. 182). In 1998 Winslow ordered a toxicity study by MBDC to check the manufacturing material for the shoes. The study was eye opening for her and served as an encouragement to present their conclusions to the top corporate management to get support for her recommendations. The main conclusion delivered to Nike leaders was that “if Nike wants to genuinely support sustainability, the thrust should be in finding solutions to eliminate waste and toxics from company products right from product conception” (ibid. 182). Her recommendation was well-received by the top management and soon Winslow was appointed (1999) to lead the newly established global division of Sustainable Business Strategies. The division defined three major environmental goals for 2020, such as Zero Waste, Zero Toxics and Closed Loop, which provided the vision for the company for the next 20 years and were included in their 1st CSR Report (CRR Nike, 2001, 17). The major ways to implement this vision and thus build corporate responsibility was education, awareness and other actions through the organization. It is very important to know that Winslow introduced her original approach to make this radical change. Instead of generating the change through management directives, she preferred to make it through people’s voluntary involvement in the project (ibid. 183). So she started multiple one-on-one meetings with the key managers and designers, convincing them over time, followed by two-day meetings with 200 key designers, managers and leaders of sustainability to discover that people at Nike are innovative and innovation is the company’s core value.

In order to facilitate absorption of the vision within company the “Team Shambhala” internal program was launched in 1999 designed and delivered by SoL-Sustainability Consortium consultants. The goal of the program was “to get the entire company—20,000 people world-wide —grounded in a way of thinking that naturally took environmental and social issues into account in every decision the company made and every action they took” (ibid. 183-184). Almost over a year, 100 persons—the most influential formal and informal leaders—among whom 65 were called “captains” (leaders from all over the world and areas of company), 35 “champions” (directors, general managers and vice presidents) went through the program “to develop their abilities to think systematically about environmental issues, accelerate their self-learning and empower them to make real-time decision in pursuit of business goals” (ibid. 184). Note that the SoL-Sustainability Consortium is an association of business leaders declared to be a “learning community” committed to more sustainable practice and strongly influenced by Peter Senge, the founder of Society of Organizational Learning (SoL) at MIT in 1997 (ibid.).

In 2010, Winslow, in summarizing the Shambhala program, underlined that it helped transform “Nike’s approach to sustainability, created 100 internal champions who launched dozens of landmark projects that continue to deliver against our 2020 goals” (ibid. 195). The program also produced 11 Maxims that express Nike spirit and guide staff activities. In this summary, she also expressed appreciation for the contributions of the Sustainability Consortium, and particularly to Senge and Elkington for helping Nike to understand the notion of sustainability from a strategic perspective, which took them some time (ibid.).

Summarizing this period one could see significant investment in HC because of education and training, consulting and advising combined with investment in SC by spending a lot of time on building lasting relations, producing trust, mutual respect and new culture based on sustainability and innovation integrated across the company. Hannah Jones, sustainability leader and VP of Sustainable Business and Innovation, stated in her talk in 2011 that engaging with stakeholders in dialogue, listening and looking back at themselves and taking responsibilities led to “massive transformation” of corporate culture resulting in understanding their full footprint, both environmental or social. This way, she added, they learned the value of working in partnership with civil organizations and others, and that “you start looking internally, changing the business processes and business systems. And I call that the Business integration phase” (ibid. 187). Based on her statement, one can assume that Nike significantly advanced the 4th—Business Integrations stage (Figure 1). Their 2005 CSR report was a landmark for the whole industry because Nike published the full list of their suppliers with their locations in the hope that other companies will follow them and through such unprecedented transparency would improve the outsourcing system. This is an act of visionary and ethical leadership, as well as entrepreneurial investment in social capital: better relations in the industry.

In 2006 Nike announced corporate reorganization to accomplish better customer service and enable better inner workings (ibid. 187). The new structure followed six categories of activities: running, men’s training, basketball, soccer, women’s fitness and sports. By 2009 Nike completed restructuring with the main goal of better “aligning its core competences with forthcoming opportunities” (ibid. 187). The restructuring led to a radical change in the CSR function to support the company’s growth strategy and facilitate transformation to a sustainable business model (ibid.). It also received a new name—Sustainable Business & Innovation (SB&I)— with a new mission to “design the future” rather than “retrofit the past”, according to its new head Hannah Jones of SB&I division and VP of Nike (ibid.). She further explained that throwing away the concept of “Corporate Responsibility” and introducing “SB&I” means that “we needed to move out of being police and move into being the architects and designers of the future growth strategy” (ibid. 188).

The new business model required a comprehensive program to get employees involved to envision Nike’s sustainable future and the role they would play. The managers went through scenario planning workshops assisted by The Natural Steps using a special tool called “the funnel” to bring the company to “a place where growth is decoupled from the scared natural resources and has far more equity built into the fabric of how wealth is disposed” (ibid. 189). This means that the company invested a lot of their resources in building SC—interpersonal relations within the company and also with their material and equipment suppliers (through the Code of Conduct and internal standards) to integrate all of them with Nike’s new business model and the “vision of a greater good” (ibid.). The integration process along the new business model was facilitated by several projects (e.g., the Nike Considered Design project to design fully closed-loop products since 2005 or the GreenXchange platform to invite organizations for collaborating in the creation of intellectual property, processes and ideas responding to sustainability-related challenges since 2010) and tools such as the Considered Index and Sourcing and Manufacturing Sustainability Index to push the company and its suppliers to be… “lean, green, empowered and equitable” (ibid. 190). Since 2011, all Nike designed shoes and approximately 98% of all newly launched products are “considered” to have the features envisioned before. (ibid.192).

These two basic numerical facts—in addition to the above mentioned implemented policies and projects—clearly confirmed that sustainability innovations spread throughout the whole company and became their competitive advantage and core corporate value. Nike reached the 4th Business Integrations stage and started moving toward the 5th Mission/Purpose stage (Figure 1). At this level of development Nike leaders realized that the term “sustainability” may no longer be an appealing vision for their employees. For that reason they substituted it (probably influenced by P. Senge) with the concept of a “Better World” as a more inspiring vision (ibid. 204-205). This new inspiring concept the company leaders started to operationalize with many efforts to “create shared vision” with their employees and then complemented with long-term contracts for fewer but more committed employees with the joint “vision of a greater good” contractors (ibid. 205). It is worth mentioning that reaching this level of development took Nike over 20 years.

4.2.2. The Siemens Case

This case is based on international students’ action research project conducted by a team of four persons from three different countries within the framework of the course “Building Sustainable Business.”‡ The company was chosen by students due to its ranking in Forbes magazine as the most sustainable global corporation in 2007, and in 2012 Siemens was awarded Best in class—Industrial goods and services by Dow Jones Sustainability Indices—and included in the Global 500 Carbon Disclosure Leadership Index for the fifth time in a row (students’ report: Assessing Sustainability of Siemens –ASoS_2017, 54). The official name—SIEMENS AG—is a global technology engineering conglomerate integrating industries such as electro-technology, energy, medical care (particularly diagnostics), infrastructure and others. In 2017 Siemens and its subsidiaries employed approximately 372,000 people worldwide and reported global revenue of around €83 billion. It is Europe’s largest industrial manufacturing company. From sustainability interests, this is one of the world’s largest producers of energy-efficient and resource-saving technologies (ibid.)

The students’ assignment was to analyze and evaluate policy recommendations of the last 10 years of company performance—2005-2016—from the point of the process of building sustainable business. For that reason, they did not take into account Siemens’ shameful past, such as using slave laborers from the Nazis’ death camps (including Auschwitz) during WWII or the huge bribery scandal from 2001-2005, which radically shook the company worldwide, and for the first time in its 170 years of existence forced them to hire an American CEO to transform the company management structure and a former German financial minister to monitor the transformation.

Overcoming their past and escaping from this ethical crisis was a great challenge for the new company leadership. For that reason, the company listed on top of its corporate responsibilities for 2005 such goals as:

- Corporate governance: commitment to financial transparency, open and honest communication with shareholders, compliance with the financial reporting requirements, and a two-tier control

- Sustainability: compliance with environmental legislations and with own environmental regulations.

- Corporate citizenship: addressing social problems by training of young people, and promoting arts and culture.

- Business practices: enforcing binding rules and guidelines to ensure ethical dealings with business partners (ibid. 48-49).

It is worth noticing that Siemens declared through these goals its commitment to invest seriously in human capital (HC), social capital (SC) and in creating shared values (CSV) for their communities—pillars of sustainable business. In addition, in 2005 the company started implementing three-year Fit4more program to strengthen its sustainable path combined with innovation leadership in the industry. An excellent example of sustainable entrepreneurship was converting restrictions into business opportunities by utilizing EU emission trading system (ETS) of greenhouse gases (GHG) in developing new technologies, increasing fossil fuel efficiency in car engines and reducing pollutions (ibid.). From the point of view of Willard’s sustainability stages, Siemens moved from the Non-compliance 1st stage to Compliance 2nd stage (Figure 1).

The next year, 2006, marked another milestone for Siemens which then introduced the new intermediate-term program Fit4 2010 to boost company growth and strengthen its corporate responsibility by meeting the following goals:

- Revising the Code of Conduct within their supply chain

- Introducing a new environmental management system (EMS)

- Reducing work accidents and occupational diseases until 2012 by implementing new Occupational Health & Safety standards

- Introducing the Corporate Responsibility Award and developing a Disaster Relief program for catastrophe prevention to achieve corporate citizenship goal

- Speeding up corporate responsibility reporting to improve monitoring of meeting performance goals (ibid.49-50).

It is worth mentioning that implementing EMS objectives initially scheduled for the year 2007 (with the objective of 85% implementation worldwide) was achieved in 2006 with the higher score of 88%. This helped the company to monitor the data of their performance more carefully. Taking into account the above mentioned data, students assessed that Siemens started moving to the 3rd –Beyond Compliance stage (Figure 1).

In 2010 Siemens made a big step toward company integration with the new program called One Siemens to boost sustainable value creation and company growth based on the three directions strategy:

- Leveraging the power of Siemens,

- Focusing on innovation-driven growth markets,

- Getting closer to customers (ibid. 51).

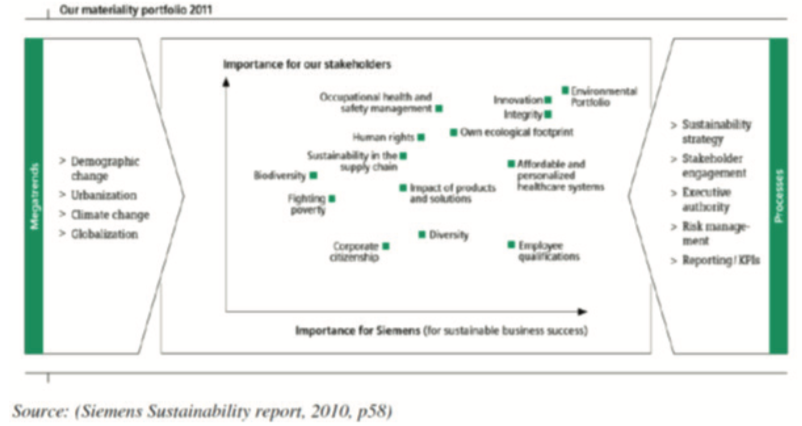

Figure 7 shows an ambitious environmental “materiality portfolio” that was to be achieved by the end of 2011 by Siemens and their stakeholders. It was a good managerial tool showing interconnections between the company and its stakeholders’ values and goals, as well as the associated challenges and risks. Some numerical data includes reducing by 300M tons GHG emissions by 2011—20% of the 2006 level—and increasing revenues from the environmental portfolio to at least 40B EUR by 2014. The intermediate reports indicate that the company was performing very well, reducing GHG by 332M tons by 2012 and increasing revenues from environmental portfolio to 33.2B EUR—two years before the deadline (ibid. 53). The successful implementation of the One Siemens program indicates that the company moved to the 4th Integrated Strategy stage of sustainable development (Figure 1), strengthening not only internal structures but also relationships with their stakeholders on the supply and demand sides.

In the move toward a more advanced stage of sustainability, Siemens has launched a very ambitious CO2 neutral Siemens program to reduce their global carbon footprint by 50% in 2020 and become a carbon neutral company by 2030 by:

- Optimizing fleet of 45,000 vehicles leading to reduction of CO2 emissions

- Buying clean power

- Investing 100M EUR in company energy efficiency improvements over the next three years

- Boosting the use of decentralized energy systems - e.g. wind, solar, energy savings and others (ibid. 55).

Successful implementation of this program, as illustrated in Figure 8, mobilized the company to initiate another program called the Business to Society (B2S) program to meet the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) by following these four steps:

- Adopting the most relevant development priorities.

- Measuring and identifying contribution.

- Drawing strategic actions that enhance contribution.

- Transparency (ibid.56 - after the Siemens Sustainability Report, 2016, 7).

The last two programs—CO2 neutral Siemens and Business to Society—indicate that the company redefined its mission to serve as a good role model of environmental stewardship and of global citizenship with a commitment to facilitate implementation of the 17 SDGs. From the point of the Willard/Senge five stages of sustainability development (op. cit.), it means that capitalizing on previous contributions and with the launching of these two programs, Siemens started moving to the highest—the 5th Purpose/Mission stage of development (Figure 1).

In summarizing Siemens’ path to sustainable company, my students emphasized the role of both external and internal sustainability drivers. The first mobilized the company’s creative and entrepreneurial HC to convert EU-level and national regulations and policies into innovations giving them competitive advantage with new technologies and processes. The second group of drivers, well-expressed in Siemens’ mission—We make real what matters—contributed to the integration of the company and its values, better self-awareness of their employees and strengthening of the brand value (ASoS 2017, 59-60). The students were also impressed with the company’s commitment to promote not only financial and environmental, but also social values. One of them—ownership culture—initiated 170 years ago by its founder Werner von Siemens was continued by his family until a few decades. This ownership culture meant cultivating long-term interests in company development, counting each employee’s contribution to the company’s success, and developing a feeling that each of them has an ownership stake in the firm expressed in commitment to excellence, innovation and responsibility (ibid.60). It is worthwhile to underline that the ownership culture proclaimed and practiced over decades had to be modified to respond to new challenges and to correct company failures particularly in ethical areas during WWII and at the beginning of XXI century after bribery scandals. For that reason the value of responsibility was further strengthened by transparency, honest communication with stakeholders, new code of conduct for the suppliers, closer contacts with customers and global citizenship. These factors indicate that the company had to respond to external and internal challenges becoming in the process a double-loop learning organization, which facilitated its path to sustainability—students stated.

4.2.3. The Carrefour Case§

The Carrefour Case (TCC) was prepared by a team of three graduate students from three different countries in EU. They decided to focus on the retailer operations of Carrefour, one of the most important segments of operations of the Carrefour Group. Initially the firm sold food products and other household items. Launched in 1959 first in France, they have since moved abroad and operate now in over 30 countries in their fully owned stores and through franchises with 380,000 employees in 12,000 stories bringing almost €104B from over 13M customers (TCC 2017, 3). The student team decided to choose Carrefour because it quickly became the number one retailer in Europe and the number two in the world just after Walmart. They were interested in how this market leader implemented principles of sustainable business (SB) and sustainable development (SD) in its strategic vision and mission, as well as, in daily practice (ibid.). The students first analyzed the development of the whole company based on company reports and then its operations in Poland and CEE, where they also conducted a series of interviews. This way they collected data to assess the process of building sustainability, including the role of the most critical types of capital—human (HC), social (SC) and the natural (NC)—in the process and finally they elaborated policy recommendations.

The company entered CEE quite late—first Poland (1997), Czech Republic and Slovakia, later Romania (2004)—due to their leadership concern in meeting high EU sustainability standards in those four countries, known in the past as very polluted and rather poor. After several years, Carrefour closed its operations in Czech Republic and Slovakia. The process of building SB at Carrefour Polska is overseen by the Sustainability Department staffed by three people located in the Quality Division in the Polish headquarters who monitor every Carrefour shop in Poland. Recently, they also monitored implementation of another EU program called the Circular Economy. The program brings a lot of benefits such as boosting the economic development and competitiveness by saving cost for the industry and making the environment more sustainable in Europe (Europea.eu, 2016 after TCC, 18). The Carrefour Polska is responsible for implementing all aspects of SD, with particular attention to sustainability of HC, SC and NC. One of the examples of such efforts is popularizing its corporate culture of openness by giving opportunity to employees to speak their mind, to enable them to be creative, and initiate their own projects (ibid. 28). This is a good example for encouraging sustainable entrepreneurship and giving every employee an influence on the company’s performance, their own self-improvement and professional growth within the company (ibid. 28). In addition, every year, the company participates in nearly 200 social agreements with its partners in France and other countries on problem solving in such areas as employment, equality of gender, disability, professional training (ibid.). For instance, in Poland they signed the Diversity Card to implement equal opportunities and anti-discrimination policies in the workplace. As a result, 800 employees with disabilities are currently working for Carrefour Polska, thanks to collaboration with the non-profit organization “PION I EKON”. Moreover, their management teams are composed of around 60% women (ibid.). The company signed the United Nations Women’s Empowerment Principles and showed explicitly their commitment through the Women Leaders program (Carrefour’s Annual Report, 2015 after ibid. 30). It is worth mentioning that Carrefour offers motivating wages and other social benefits adapted to local conditions to boost collective performances and knowledge sharing among their employees. They also invest heavily in HC by providing a variety of training and workshops—in 2015 over 5.1 million training hours. In 2016 one of their training priorities was using new technologies (ibid. 30 from Carrefour’s Annual Reports, 2015 & 2017).

Besides investing in HC, Carrefour paid attention to investing in Social Capital (SC) both within the company and with its suppliers. Commitment to cooperating with its suppliers and sharing knowledge with them in identifying their most beneficial development targets produced a unique competitive advantage over its competitors. (ibid. 31) One of the best examples was increasing support to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) by simplifying local product preferences and introducing financial support schemes. This way the company within several years was able to increase the share of locally produced items (in the case of food up to 74%) and most importantly, creates wealth in the regions of Carrefour operation, and significantly reduces pollution from transportation. Carrefour Quality Lines program has engaged more than 21,000 producers to commit themselves to follow quality and sustainable goals set by them (ibid. 32). These are concrete indicators of enormous effectiveness of investments in SC.

This is also an excellent example of creating shared value (CSV) to customers by focusing on improving the economic stability and progress of suppliers’ product quality, as well as ensuring enhanced safety and traceability of core products (ibid. based on Carrefour Annual Report, 2015). The company has also introduced a self-assessment tool that its suppliers can use to compare themselves to other suppliers in terms of sustainability practices and assess if there is a need for corrective actions and improvements. In addition to sustain their suppliers’ proactive behavior in designing and sharing sustainability innovations, Carrefour has been giving prizes to best ideas in events such as Supplier’s Major Challenge for the Climate Change since 2015. Furthermore, projects such as Inbox in France give suppliers access to Carrefour’s employees’ expertise and thus, allow suppliers with an insufficient knowledge and resources to build up their businesses according to the high standards of one of the leading retail brands in CEE region (ibid. based on Carrefour Annual Report, 2015). The students evaluated the relationship between Carrefour and its suppliers as a great example for benefits of investments in social capital which produces high level of trust and clear rules and norms for everybody. It also indicates strengthening the integration process within their supply chain, a marked feature of the 4th stage– Company Integration (Figure 1).

In building SB, the company invested in NC conservation and improvements as the foundation of other forms of capital. This is particularly important for Carrefour because healthy NC is the main base for food products produced and sold by the organization. In this case the company has established four pillars of sustainability policy, two are directly related to protecting the environment (ibid. 35-37):

- Combating Waste:

- In order to reduce food waste, Carrefour regularly donates food to local food banks. For example, in Poland, Carrefour has invested in fourteen refrigerated vehicles to ensure the preservation of the quality of the food sent to Caritas and other non-profit organizations.

- As a part of the circular economy programs the company stored rainwater in some selected stores and reused it to clean floors and car parking areas.

- Since 2013, the stores have also started a new project to reuse the bio-methane produced by spoiled fruits, vegetables, and flowers from their stores and started using it as fuel for their trucks. This project is limited to some selected urban areas in France but the company aims to expand it in the future as part of its objective to reduce CO2 emissions.

- Carrefour has pledged to decrease its CO2 emissions, and as a result of their partnership with the UN Conference on Climate Change that took place in Paris in 2015, the retailer set clear goals for better use of its energy. As described in their website, they aim to reduce CO2 emissions by 40% by 2025 based on their 2010 levels. Their long-term goal is to reduce emissions by 70% by 2050. So far, in 2015, they have already managed a decrease of CO2 emissions by almost 30% in terms of the 2010 level (Carrefour.com, 2017).

- Protecting Biodiversity:

- The agro-ecology, the Quality Line is the largest program that includes the efforts of both Carrefour and its suppliers committing to reducing the use of pesticides, to rotating crops, and to refrain from treating soils chemically (Carrefour.com, 2017). The company is dedicated to selling animal products using animals that were not fed with antibiotics. This concerns fish, chicken, and eggs in particular. The retailer also implemented beekeeping above some of its stores in France and Poland to help reduce the disappearance of bees (ibid. 34).

- Carrefour promotes sustainable fishing. This is why they pledged to stop deep-sea fishing since 2007. (Carrefour.com, 2017).

- Another example of Carrefour’s resolution to limit the negative impact of its operations concerns palm oil. They have managed to source 100% of the palm oil used in their brand products from sustainable sources. Indeed, all of the palm oil suppliers were certified by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (Carrefour.com, 2017). This fits within the company’s overall goal of protecting forests around the world.

- Carrefour’s efforts toward sustainability include also its suppliers. The self-assessment tool, Autodiagnostic, is an example of Carrefour’s work toward expanding their sustainability standards throughout their entire supply chain (ibid.).

Although the examples of building environmental sustainability indicate that the company is a leader among major retailers in sustainable practice and initiative, thereby making progress in company integration (Stage 4th), the students discovered, however, through interviews and field visits that franchised stores do not have the obligation to meet sustainability standards of Carrefour Group, and every country is not on the same level with actions taken towards sustainability in other branches. For instance, the implementation level is very advanced in France but less advanced in Poland (ibid. 35). Since customers tend to associate these stores to the Carrefour brand, such differences within an organization can have a negative impact on the company’s image and reputation. Moreover, it seems that the extent to which independent stores commit to sustainability objectives vary significantly between countries. For instance, whereas the stores in France are continuously following the latest initiatives introduced by the headquarters, branches in Poland are yet to come to terms with such embedded activeness (ibid. 36). Therefore, in order to get to level 5, they would need to rethink their vision and mission in relation to sustainability. For that reason, the students elaborated two recommendations:

- First: Carrefour needs to take a tighter control of the company branches abroad and on franchises by putting requirements on them to adopt and follow the same sustainability goals as the corporation has stated its organization strategy.

- Second: As the second largest global retailer and a quite successful leader in implementing sustainable practices within its supply chain, Carrefour should take leadership and more responsibility to teach their customers to change their consumer behavior to meet the demands of the growing sustainable society. These initiatives among others could include providing guidance for improved recycling methods as well as helping the consumers to reduce the usage of plastic material including shopping bags and packages. They could also educate their customers about facts regarding environmental impact of certain products, how to reduce their negative ecological imprint and increase social benefits of fair trade. Carrefour could work on convincing their customers that consuming ecological products creates not only additional benefits to them (e.g. healthier diet) but also produces environmental gains for the global community and ecosystem. This way, showing additional values of such products, the company could boost a greater demand among customers and thus increase its business. This “win-win strategy” Carrefour has already implemented with its suppliers. So it would be a natural extension to do this on the consumption side.

5. Conclusions & Recommendations

The author explored existing opportunities—in theory and in practice—to educate a cadre of champions for sustainability or a better world—sustainable entrepreneurs based on the concept of sustainable business (SB), as a learning organization (LO) introduced by Peter Senge (1990) and recently popularized by Dan Oncica and Dan Candea (2016). After analyzing several models of SB and recent development in defining sustainability, including the four dimensional model of Joachim H. Spangenberg (2007, 2008), he moved to three practical cases of global corporations—Nike, Siemens & Carrefour—studied in the graduate course on Building Sustainable Business (BSB) delivered last year at the Kozminski University in Warsaw, Poland. The author came to the following conclusions:

- The concept of SB as a learning organization is a good foundation for educating about sustainable entrepreneurship (SE) and/or entrepreneurs.

- The experience based on delivery of the BSB proved that the fourth dimension of sustainability—Institutional, linked with values (culture) such as democracy, justice and care—is very important at every level of human activities—from a business firm or any community organization level to regional, national and global levels. For that reason, it makes sense to move from the triple-bottom-line (TBL) symbol of sustainability to the quadruple-bottom-line (QBL).

- Careful analysis of the selected cases confirmed that education—formal, informal and self-education—is a powerful force for shaping new leaders and entrepreneurs for SB within a framework of the learning organization (LO) concept.

- The action research projects selected by students proved that there is a good chance for change toward SB, even in large global corporations by utilizing both external and internal forces influencing their behavior and strategic decisions.

- The internal forces—the main focus of this paper, could become effective tools in building human (HC) and social capital (SC), and conserving natural capital (NC) for sustainable development (SD) or—using a more updated term—a better world.

- The case studies show that an unlimited creativity of business entrepreneurs (HC) could offer much greater variety of internal policy tools (incentives, projects, programs, codes of ethics, standards, etc.) than external (regulatory) policies toward SD. This way, turning sustainable entrepreneurship for creating shared values and win-win solutions for all participants/shareholders helped companies moving within the Virtue Cycle and avoiding traps of Vicious Cycles created often by external forces.

- The selected cases confirmed that the largest resource allocation in the business sector (compared with public or civic sectors – Porter 2013) could be utilized toward sustainability or a better world if there is visionary leadership combined with SE, systemic approach and long-term strategy. This is not an easy and simple process, but it is possible to succeed.

- The BSB course with its community learning design might be regarded as an effective approach in shaping new SE based on the enterprise as an LO and team work.

- The student-centered approach of the BSB delivery boosted critical thinking and the application of creativity tools taken from the LO concept in practical cases.

- Finally, sharing the action research results with their stakeholders at the end of the course contributed to building students’ responsibility for solid work during the semester and gave them the opportunity to share the fruits of their project successes.

Based on the above mentioned conclusions, the author proposes the following recommendations for building sustainable businesses:

- The academic community, particularly associated with World Academy of Art and Science (WAAS) and World University Consortium (WUC), should popularize the quadruple-bottom-line (QBL) approach to sustainability and sustainable business and/or organization (SB) and this way replace the traditional TBL approach.

- WAAS should further discuss the roles of non-material capital—intangible assets—particularly HC and SC, and improve the measurements of their values compared with other forms of capital in its New Economic Theory (NET) program.

Both organizations—WAAS and WUC—should popularize courses such as BSB that contribute to strengthening internal forces of change toward SD within companies.

Teaching BSB courses in advanced economies has a significant role to influence future corporate leaders—particularly MNC—thinking about global sustainability—better world—which have their HQs located in the part of the world. However, this teaching is vital in developing and emerging economies, where they badly need sustainable entrepreneurs to move their citizens out of poverty. These economies meet their basic needs and push on sustainable path of development based on innovations and are focused on avoiding mistakes committed before by advanced economies.

Bibliography

- Archibald, S., Bochniarz, Z. 2003. Environmental outcomes assessment: Using sustainability indicators for Central Europe to measure the effects of transition on the environment in David E. Ervin, James R. Kahn and Marie Leigh Livingston (editors) Does Environmental Policy Work? Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, Northampton, MA, USA, 2003, pp.83-113.

- Archibald, S., Bochniarz, Z., 2005. Market Liberalisation and Sustainability in Transition: Turning Points and Trends in Central and Eastern Europe in JoAnn Carmin & Stacy D. VanDeveer (editors) EU Enlargement and the Environment: Institutional Change and Environmental Policy in Central and Eastern Europe, Routledge, London and New York, 2005.

- Archibald, S. O., Bochniarz, Z., 2006. Assessing Sustainability of the Transition in Central European Countries: A Comparative Analysis, in Zbigniew Bochniarz and Gary B. Cohen (editors) The Environment and Sustainable Development in the New Central Europe. Berghahn Books, New York-Oxford.

- Archibald, S. O., Bochniarz, Z., 2009. Transition and Sustainability: Empirical Analysis of Kuznets Curve for Water Pollution in 25 Countries in Central and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States, Environmental Policy and Governance, Vol. 19, Issue 2.

- Bellah, R., Madsen, R., Tipton, S.T.M, 1992. The Good Society.

- Bochniarz, Z., 2008. Economist’s Reflections on Varieties of Capitalism, Transformation and the State of Comparative Economic System Research in Satoshi Mizobata (editor) Varieties of Capitalisms and Transformation, BUNRIKAKU publisher, Kyoto, Japan, 2008, pp.149-161;

- Bochniarz, Z., 2013. An Economist’s Reflections on Individuality, Human and Social Capital, and Responsibilities of Academia in Eruditio Vol. 1, Issue 2 February-March 2013;

- Bochniarz, Z., Bolan, R.S. 2004. Building Institutional Capacity for Biodiversity and Rural Sustainability (co-author) in Stephen S. Light (editor) The Role of Biodiversity Conservation in Rural Sustainability IOS Press, Amsterdam, 2004, pp. 79-94.

- Bochniarz, Z., Faoro, K., 2016. The Role of Social Capital in Cluster and Regions’ Performance: Comparing Aerospace Cases from Poland and U.S.A. (co-author), in Malgorzata Runiewicz-Wardyn (editor), Innovations and emerging technologies for the prosperity and quality of life, PWN, Warszawa.